Five charts on Japan ahead of the election

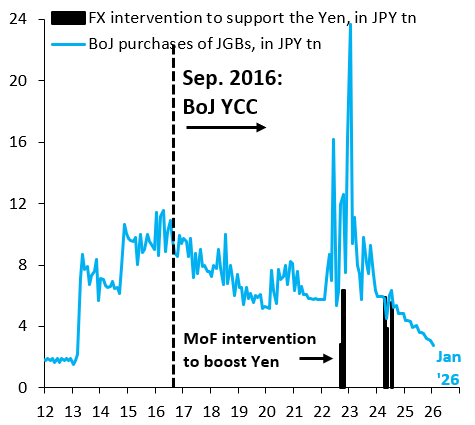

Yen weakness is increasingly a political liability in Japan. Voters recognize it pushes up import prices and hurts consumers, while exporters benefit. Yen weakness thus has important distributional consequences, which is why the government encouraged all the recent chatter about FX intervention. This stopped $/JPY from going above 160 ahead of the election, something that would have made life hard for Takaichi.

The election takes place tomorrow and it’s fair to say there’s a lot of lethargy on the Yen. Markets think the recent “rate check” by the NY Fed caps $/JPY at 160, but that’s nonsense. With the election out of the way, especially if Takaichi does well, the optics of Yen depreciation won’t matter nearly as much. So the election is conceivably a catalyst for the next round of Yen weakening.

The basic problem for the Yen is that the Bank of Japan (BoJ) remains a large buyer of Japanese government bonds (JGBs). This caps long-term yields, which are still much too low given Japan’s high public debt. Risk premia are being artificially suppressed in the bond market, which means they show up – instead – in currency markets, where they put depreciation pressure on the Yen. Today’s post shows five charts on Japan that summarize this conundrum and suggest a way out.

-

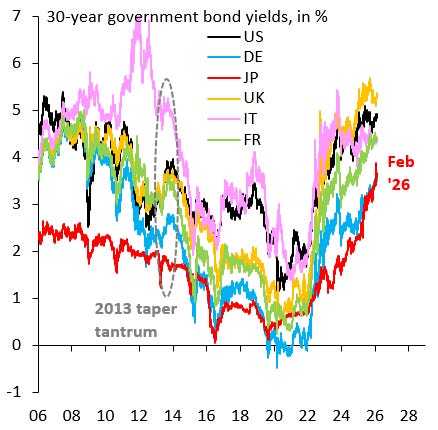

The rise in Japan’s long-term yields is misleading. Japan’s 30-year government bond yield has risen to its highest level ever, as the red line in the chart below shows. One common misconception is that this rise should stabilize the Yen or even help it rise. That can’t and won’t happen as I explain next.

-

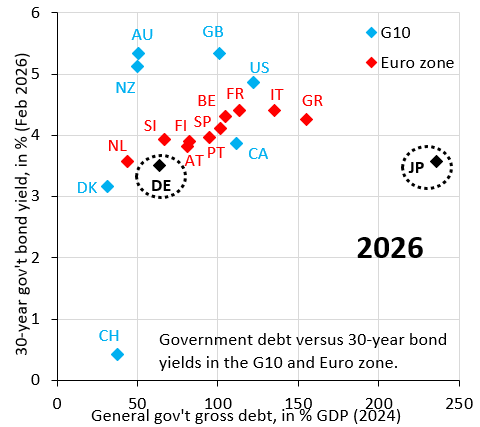

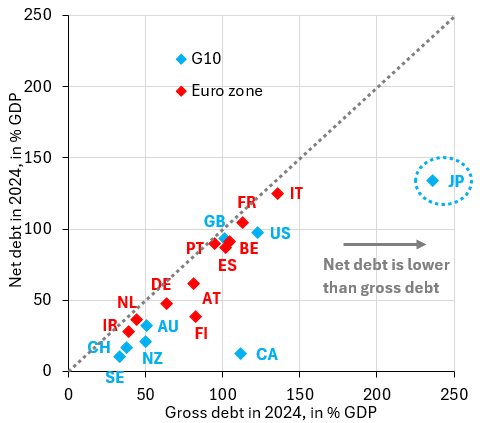

Long-term yields are still much too low given high public debt. The chart below has gross public debt in percent of GDP on the horizontal axis and yesterday’s 30-year government bond yield on the vertical axis. Japan’s 30-year yield is the same as Germany, which makes no sense given how much higher its public debt is. This is the easiest way to see that Japanese yields are being kept artificially low, which prevents them from accurately pricing risk premia to reflect Japan’s high debt.

-

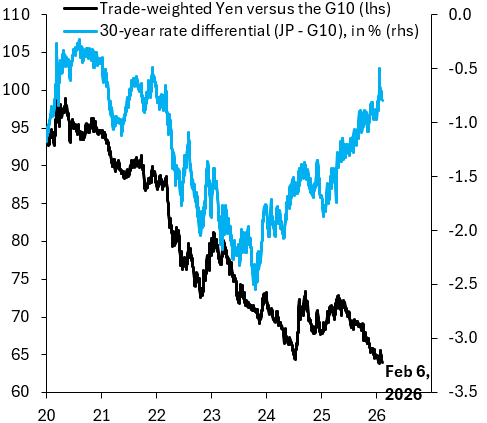

Yield caps mean fiscal risk premia put depreciation pressure on the Yen. A common misconception is that the rise in Japanese long-term yields should stabilize the Yen. That’s wrong. What matters is how yields compare to what markets would like to see without BoJ intervention. It’s likely that these “shadow” yields are much higher than observed yields and that the gap may have widened. This explains why the Yen yesterday fell back to its lowest level in trade-weighted terms in a very long time, as the black line in the chart below shows.

-

Depreciation pressure will continue as long as BoJ buys JGBs. As the blue line in the chart below shows, the BoJ remains a large buyer of JGBs in gross terms. As long as this continues, fiscal risk premia are being artificially suppressed in the bond market, which means they instead show up in currency markets, putting depreciation pressure on the Yen.

-

There is a way out from this debt trap. Japan’s government has lots of financial assets, which is why net debt is so much lower than gross debt. The chart below shows gross debt at 240 percent of GDP on the horizontal axis, while net debt is only 130 percent on the vertical axis. Not all of these assets are liquid, but some of them can be sold in short order, with the proceeds used to pay down public debt. Even a gesture in this direction would go a long way.

As long as Japan threatens things like FX intervention, it’s a sign the country is trapped in denial. Japan has the means to get itself out of this debt trap, but to get there it’s fair to say that things have to get worse before they get better. The Yen has to fall further before vested interests agree to sell the government’s financial assets.