Bessent Falsely Blames Japan For Stock Market Revolt Over Trump Threats Over Greenland, Part 1

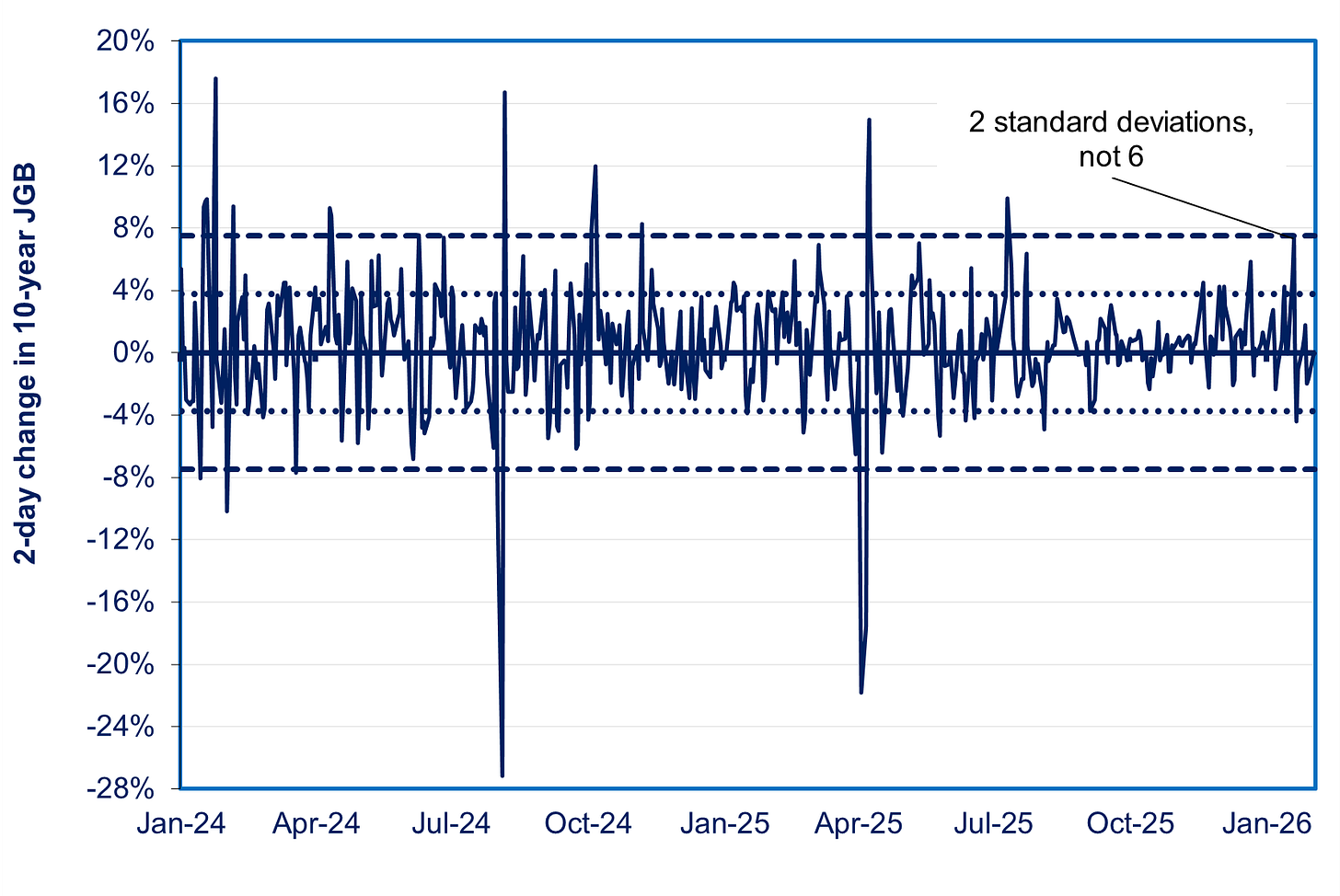

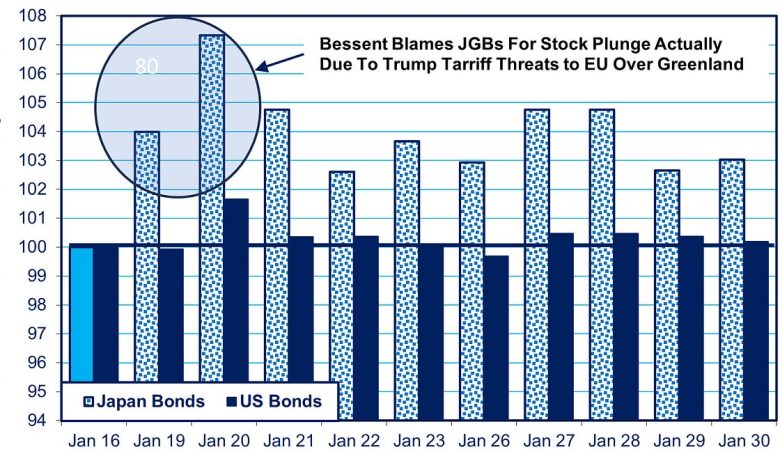

Source: Wall Street Journal Note: This is a rise in percent, not percentage points, e.g., on January 20th, the yield on ten-year US Treasury bonds rose from 4.23% to 4.30%, a rise of 17%.

Bear with me as I comment on news from two weeks ago, since I believe it has a great bearing on the future: actions by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent that give ammunition to fearmongers. The latter prophesy that rising Japanese interest rates will not just have some impact on American finances but will wreak havoc. This situation arose from Bessent’s efforts to defend Donald Trump’s threats regarding Greenland by blaming Japan for the financial turbulence turmoil Trump had created.

On Saturday, January 17th, Trump vowed to impose an additional 10% tariff on eight European countries by February 1st. He added a threat to raise the rate to 25%. The “provocation” was that Europe had dared to oppose his efforts to seize Greenland from Denmark. Seven EU nations even sent small military contingents to protect Greenland. If carried out, Trump’s action would have ended NATO, a hitherto unimaginable gift to Vladimir Putin. So, when markets opened on Monday in Europe, stocks plunged 1-to-1.5%, and when they opened on Tuesday in New York, they nose-dived 2%. In addition, the interest rate on U.S. government bonds rose by 1.7% (not 1.5 percentage points; see the chart at the top and the accompanying note). The uproar would have been much greater except that Trump only carries out his tariff threats 27% of the time, giving rise to the “TACO (Trump Always Chickens Out) Trade” in financial markets.

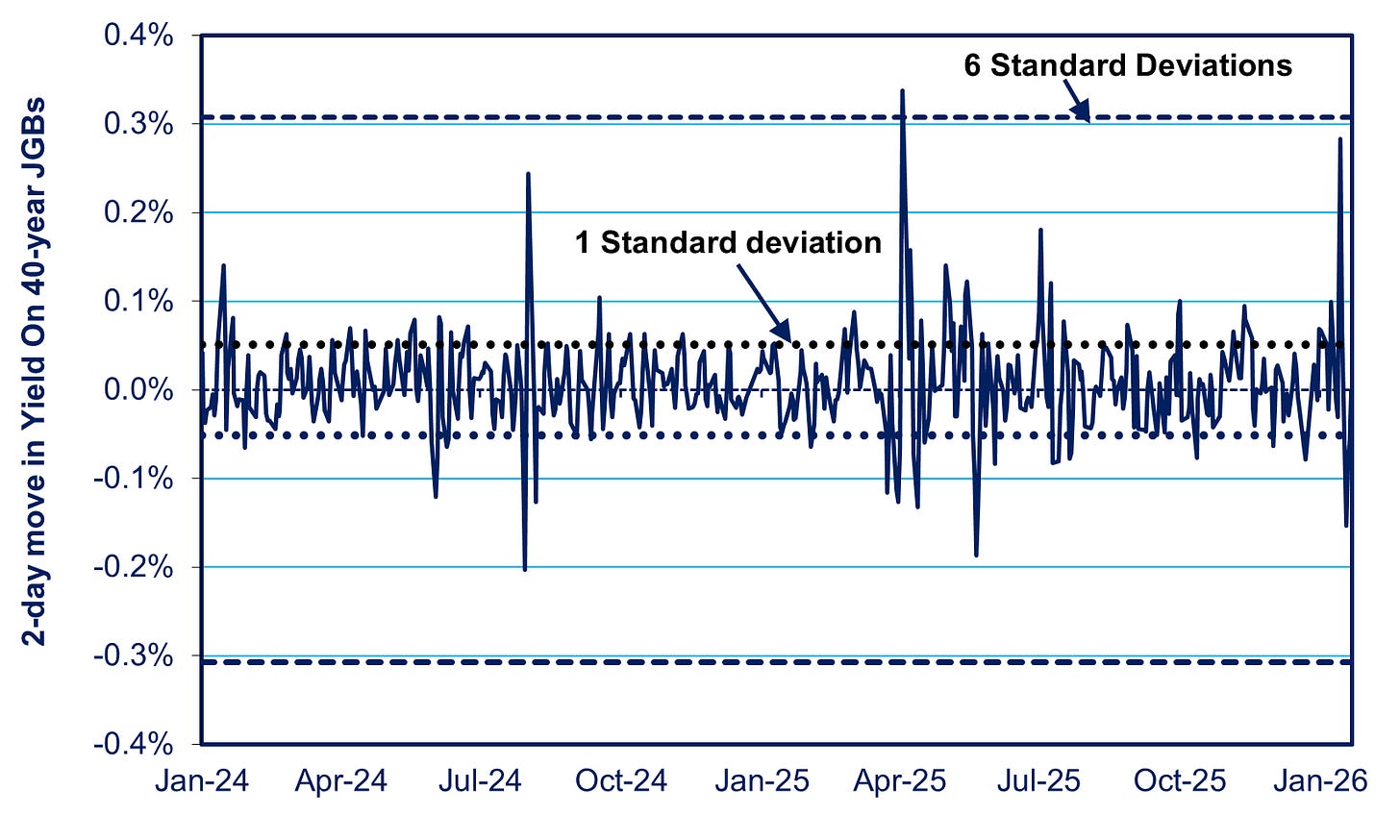

Trump’s tantrum happened to coincide with a rise in yields on Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) due to Prime Minister Sanae Takichi’s January 19th announcement of a big fiscal stimulus package (see again chart on top). Bessent seized on this to con people into believing that the market turmoil arose from the JGB situation. He brazenly contended, “I think it’s very difficult to disaggregate the market reaction from what’s going on endogenously in Japan. Japan over the past two days has had a six standard deviation [i.e. a very extreme] move in their [government] bond market…and that that was happening before any of the Greenland news.” Unfortunately, he succeeded in getting a lot of the press to repeat this canard.

And then Bessent went full-on Trump with his bully-boy rhetoric. “Denmark’s investment in U.S. Treasury bonds, like Denmark itself, is irrelevant [emphasis added].”

Bessent’s Lies

Hitherto, Bessent had not sullied his name with the obvious lies that come so easily to his boss and other minions. But, at the Davos conference where he was when this all unfolded, he behaved just like his cabinet colleague, the Secretary of Homeland Security. Three deceptions marked his assertions.

1) For one thing, on everyone’s calendar except Bessent’s, a Trump threat made on Saturday comes before a Japanese interest rate hike the following Monday and Tuesday.

2) Talk of a six standard deviation move is not a lie but does mislead. Bessent omitted that this occurred only in the superlong 40-year JGB, whose thin trading volume makes it prone to excessive volatility. His wording implied that this volatility applied to the overall bond market. Standard deviation is where two thirds of the data points are located above and below the average level. The 40-year bond accounts for only a tiny share of outstanding JGBs, and small trades can cause it to gyrate wildly. On 19-20, a tiny $280 million in trading sent the 40-year JGB careening upwards and then it fell back down again. This has happened twice before in the last 18 months without causing international ripples (see the first of two charts below). To see the real situation, look at 10-year JGBs, the core of the $7 trillion JGB market. They moved just two standard deviations, something that happens on 5% of the trading days. It was a smaller move than some others in the past two years (see second of the two charts below). Bessent knows all this, of course, but he was desperate to blame someone else for the consequences of his boss’s blunders, a common assignment in this administration.

Source: Author calculation based on MOF data at http://www.mof.go.jp/english/jgbs/reference/interest_rate/index.htm

Source: Author calculation based on WSJ data

1) Most importantly, the stock plunge had nothing to do with Japan. How do we know that? Because markets only calmed after Trump publicly renounced earlier hints at using force to steal Greenland as well as his vow to impose new tariffs. He claimed that a “fabulous” deal regarding Greenland made the tariffs superfluous. In reality, the supposed deal gave him nothing more than a figleaf. “Fabulous,” you may remember, stems from “fable.”

The rapidity of Trump’s U-turn makes me wonder whether Bessent told his boss the truth: that it would take another TACO to end the market revolt. Still, Trump has destroyed trust in America among its closest allies. And Bessent’s lies add a bit of unnecessary anxiety to the financial markets when his job is to keep them stable.

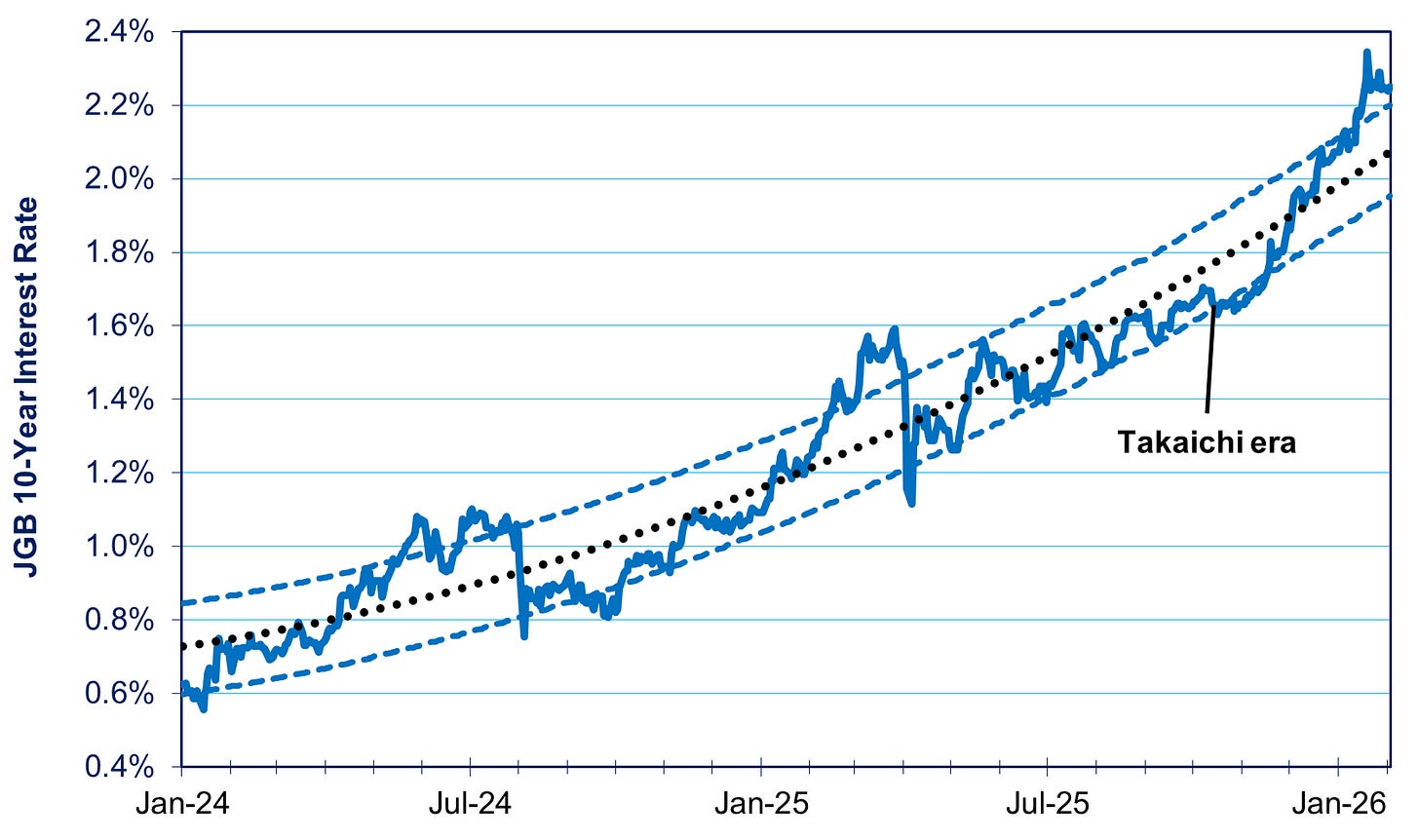

Core JGB Interest Rates Rising in Slow, Steady Manner

Let’s be clear: despite Bessent’s myths and some sensationalist press talk of “chaotic” markets, nothing panicky is going on vis-à-vis Japan’s JGBs. Today’s rates are close to the normal fluctuation range since the BOJ ended “yield curve control” and let markets determine the long-term interest rate (see chart below). For more on this, see my previous post.

Note: Dashed lines refer to a “standard error,” meaning that the interest rate on two-thirds of the trading days lies between the two dashed lines

Let’s see what is causing rates to rise and what that may tell us about future rates. The headline rate you read about, around 2.24% these days, is the result of two economic factors. The first is an “inflation premium.” This is the rate that investors demand to cover the cost of expected inflation over the coming decade. If investors don’t at least cover the rise in prices, their real net return would be zero. The second factor is the “real” interest rate, i.e., the real return that investors receive after accounting for inflation.

In Japan, most of the rise in the headline rate is due to a hike in the inflation premium. We know that because Japan, like other countries, issues a small amount of inflation-indexed bonds, called the JGBi. The so-called “breakeven rate” on a JGBi shows bondholders’ inflation expectations over the coming ten years. In January 2024, the breakeven inflation rate was 1.3%. As of December 26 (the latest I have), it had risen to 1.8%.

On December 26, the yield on regular 10-year JGBs was 2.05%. So, the “real” interest rate—the nominal yield minus the inflation premium (2.05% minus 1.8%)—was a mere 0.24%. That is extremely low. But it is determined by the supply and demand for long-term credit in the market for government and corporate bonds, bank loans, and other instruments. It therefore reflects the fundamental economic situation in Japan. In the last month, the JGB rate has since risen to around 2.25%, a rise of just 0.2 percentage points. It will take time to see how much of this is due to a rise in the inflation premium and how much is due to a rise in the real return. Both would be normal responses to Takaichi’s fiscal largesse. In any case, this is hardly wild and crazy market; it is one trying to return to normality after a long period of deflation.

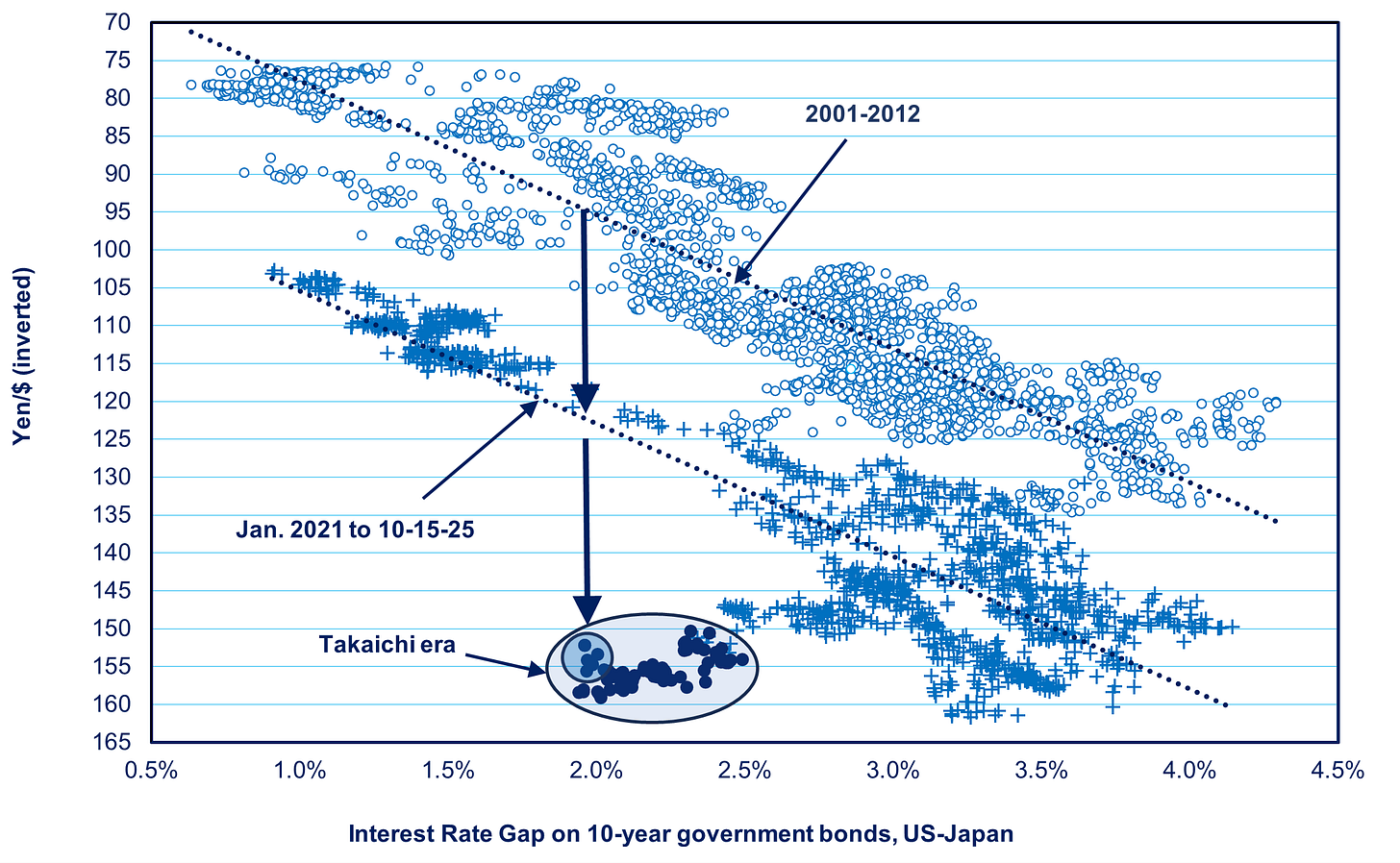

Yen Moves A Tiny Bit Stronger—For Now

On Jan. 23rd, the New York Federal Reserve, on behalf of the US Treasury, asked Wall Street financial institutions about yen-dollar currency transactions. The market felt this meant that Tokyo and Washington were preparing a joint currency intervention. That would be far more powerful than a lone move by Tokyo. As a result, the yen’s value strengthened 4%: from ¥158.4 on Jan. 22 to ¥152.2 on the 28th. But once Bessent said the US had not intervened and refused to comment on whether it would do so in the future—which market players took as a sign that the US would not intervene—the yen began to retreat again. As of today, the yen is around ¥155.4.

In any case, movements up or down by just a few points don’t change the essentials. The yen remains quite weak, considering that the interest rate gap between American and Japanese 10-year government bond rates is just 2%. The last time the gap was this narrow, in 2022, the yen was valued at ¥125 (see chart below). As I’ve long argued, the yen is weak because the Japanese economy and export competitiveness are weak.

Note: Dots in the light blue oval cover the period since it became clear Takaichi would become Prime Minister; dots in the darker blue cover the period since the Fed asked Wall Street about yen transactions.

Takaichi Changes Her Tune, But Denies Having Sung Her Earlier Song

One factor adding to downward pressure on the yen is taking Takaichi at her word that she favors a weak yen, a view she proclaimed yet again just a couple of days ago.

Now, however, Takaichi has changed her tune and denies saying what she so recently declared. On Saturday, she proclaimed: “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity. Whether it’s selling food or automobiles [emphasis added], even though there were U.S. tariffs, the weaker yen has served as a buffer. That has helped us tremendously.”

It’s unbelievable that she mentioned food, because the weak yen is one of the major reasons food prices are up 30% from four years ago, and public outrage over this cost her Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) its majority in the Lower House in the 2024 elections. Now, the LDP has to face the electorate in a “snap election” on February 8th. Since food comprises 27% of the household budget—very high compared to other rich countries—this issue is a big deal.

The opposition seized on her gaffe (defined as shouting out loud what she really feels). Yoshihiko Noda—a former Prime Minister and co-head of the newly-created opposition coalition party, the Centrist Reform Alliance—stated, “No one feels pleased while looking at their household budget amid an excessive weakening of the yen. The perspective of ordinary people is missing.”

Perhaps realizing her unforced error, Takaichi lamely claimed in a post on X, “I did not say which is better or worse — a strong yen or a weak yen. My intention was solely to state that we aim to build an economic structure that is resilient to exchange-rate fluctuation, and not, as some reports have suggested, to emphasize the benefits of a weak yen.”

In any case, polls predict that the LDP will win solidly on Feb. 8th, perhaps even gain a two-thirds majority.

NOTE: In Part 2, I’ll refute the notion that US financial markets are due for big tremors as a result of rising interest rates in Japan causing a decline of the “carry trade.” The short message is: the carry trade has been substantially unwinding for two years; if it has not caused tremors so far, why would some further unwinding wreak havoc now?

Paid subscribers will be eligible for my new mini-posts (see this for more info). Beyond that, if you feel you’ve gained insight from this blog, ever restacked it, if you ever subscribed to my previous publication, The Oriental Economist Report, and certainly, if you or your firm have gained insights that helped guide your investments, please support the blog with a subscription or by “buying me a cup of coffee.” You can buy a cup or two on a one-time basis, or once a year, or once a month.