Economic experts reflect on Trump’s year back in office

A year into his second term in the White House, President Donald Trump insists that the U.S. has become the “hottest country anywhere in the world.”

“Under our administration, growth has exploded, investment is booming,” the president told the Detroit Economic Club last week. “Inflation is defeated. America is respected again like never before.”

Among some of the impactful actions he has taken to reshape the economy, Trump has levied sweeping tariffs on most countries around the world, sought to reshape the Federal Reserve board and signed into law a measure that permanently extended many 2017 tax cuts, reduced funding to social service programs, and upped spending on border security and defense.

“It’s been quite a wild ride,” said Eric Talley, a professor of law and business at Columbia Law School.

Ahead of the one-year anniversary of Trump’s second swearing-in, Spectrum News spoke to Talley and several economists to gauge the impact of the president’s policies and what could be in store for the future.

Shipping containers are seen ready for transport at the Guangzhou Port in the Nansha district in southern China’s Guangdong province, April 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File)

Sweeping tariffs placed on most U.S. trading partners

Shortly after taking office, Trump announced the first set of tariffs he was imposing under the International Emergency Economics Powers Act, or IEEPA. He declared the influx of synthetic and illicit opioids from China, Canada and Mexico into the U.S. to be a national emergency, necessitating actions by executive orders.

Two months later, the president unveiled what he called his “Liberation Day” import duties, consisting of a 10% baseline rate on nearly all of the U.S.’ global trading partners as well as country-specific rates roughly tied to their respective trade surpluses that the president dubbed “reciprocal” rates.

Jai Kedia, a research fellow with the CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank, called the process “chaotic.”

“I don’t think the administration thought markets would react the way it did to the initial billing of tariffs,” he said, noting the stock market sell-off in early April.

After a 90-day pause, the “reciprocal” tariffs went into effect and have been followed by announcements of various additional duties on specific countries and industries.

“They have continued in place with some changes –– sometimes dialing them down, sometimes dialing them up, sometimes the introduction of new ones or the reintroduction of previously announced tariffs,” Talley said. “It’s still very early days.”

Most recently, the president said he was levying a 10% tariff on eight European countries Saturday for their opposition to a U.S. takeover of Greenland.

But the fate of tariffs imposed under IEEPA remains unclear as a decision by the Supreme Court looms. The nine-member panel heard oral arguments in a consolidated case brought by several small businesses and Democratic-led states in November.

A ruling by the nation’s top court could come as early as Tuesday, and there are a number of potential paths forward –– including affirming Trump’s authority to issue tariffs under IEEPA or invalidating the import duties and requiring the federal government to issue refunds to importers. Trump said the latter would be a “terrible blow” to the country.

“That was one of the issues that the Supreme Court was actually trying to deal with in oral arguments,” Talley said, “How do we even deal with… trying to claw back the toothpaste that’s already come out of the tube?”

Customs and Border Protection said in December it had collected more than $200 billion from new import taxes last year between Jan. 20 and Dec. 15, crediting dozens of executive orders issued by Trump since he began his second term. An estimated $133.5 billion of that figure came from the IEEPA import duties being considered by the Supreme Court –– with some estimates putting that number now at $150 billion.

Hundreds of companies, including retail giant Costco, have filed legal challenges to protect their right to refunds ahead of the decision, and some businesses have separately been using different strategies to mitigate the import dues.

“We saw a big sea change in the way that the U.S. kind of thinks about buying imported goods,” said Ryan Monarch, an associate economics professor at Syracuse University

The Budget Lab at Yale University estimated late last year that the overall average effective tariff rate in the U.S. had risen to 16.8% –– the highest it has been since 1935 — and had fluctuated from 2.4% in early January 2025 to peaking at about 28% around the time of Trump’s April tariff announcements.

“It’s been a volatile year in terms of the level of tariffs and the effect on the global economy, but they seem to have settled down now,” said Phillip Braun, a finance professor at Northwestern University.

The effects of the tariffs have also been visible on the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services, which narrowed in October to the lowest monthly total since 2009, according to data from the Commerce Department. The report, released in January, also showed that the overall trade deficit from January to October last year increased 7.7% compared to the same period in 2024.

“Before the tariffs were imposed, we saw a huge increase in imports,” Monarch said. “Why is that? That’s because people were trying to get ahead of the tariffs. They were trying to stock up their inventories before those higher costs came into place. That was followed by a huge drop-off in the imports after the tariffs were in place.”

Monarch noted that the majority of goods and services are produced domestically. Imports corresponded to about 14% of U.S. gross domestic product in 2024, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. But for certain products –– such as fruits and vegetables –– the U.S. is heavily dependent on other countries.

“If you’re looking in the right places, you’re seeing big price increases as a result of these tariffs,” Monarch said.

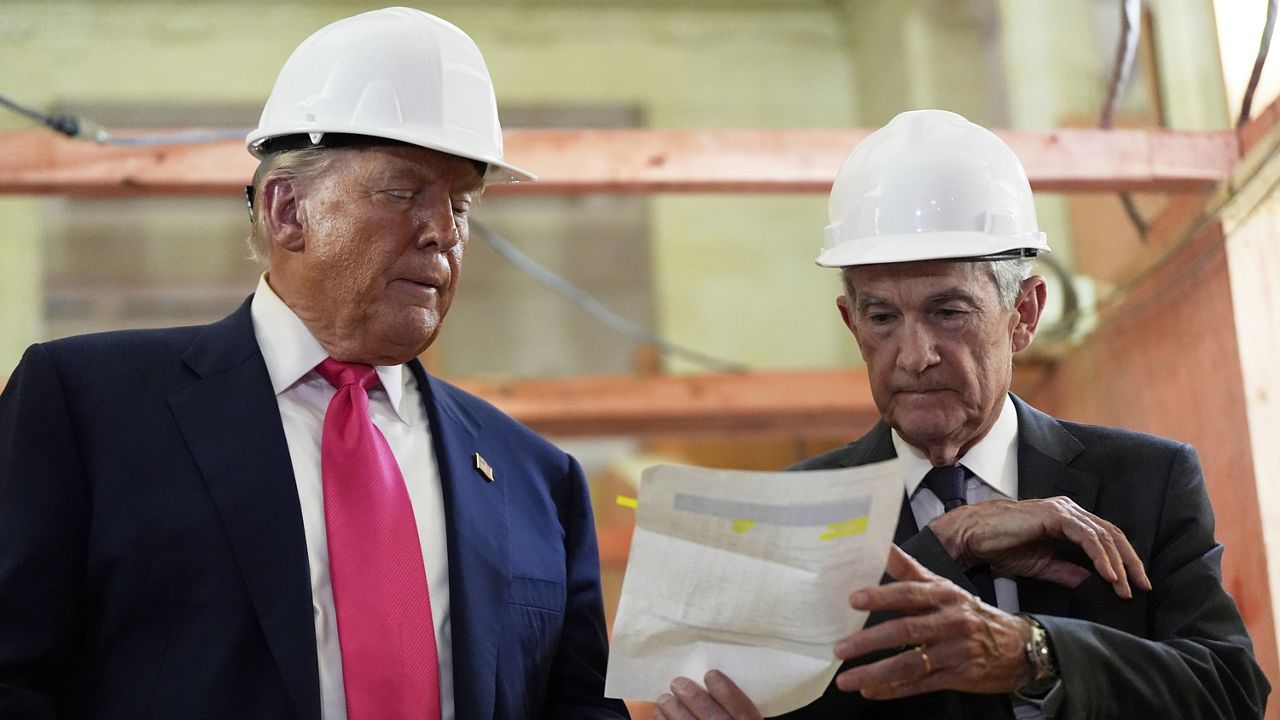

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, right, and President Donald Trump look over a document of cost figures during a visit to the Federal Reserve, July 24, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

Pressure on the Federal Reserve

Since returning to office, Trump called for the Federal Reserve to lower the federal funding rate — the interest rate at which banks charge one another to hold money.

Oftentimes, other lenders follow suit when this rate increases or decreases, which then impacts how much consumers pay to borrow money for items such as homes and cars.

Lower interest rates also mean less money the federal government needs to spend to pay the interest on the national debt, which the Treasury Department says now stands at $38.45 trillion and costs $355 billion –– or 19% of federal spending in fiscal year 2026 –– to maintain.

In apparent frustration at the current interest rates, the president has derided Fed Chair Jerome Powell. In his first term, he called the Fed chair, whom he nominated for the position, an “enemy,” and the president’s rhetoric appeared to intensify in 2025 with Trump openly musing about replacing Powell.

“Fed Chair Jerome Powell has had a very cool response to all of this pressure over this year,” said Monarch, who previously worked as the principal economist for the International Finance Division of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. “That changed with an extraordinary statement by the Fed chair on Sunday night, last Sunday.”

Powell announced that the central bank has been served with subpoenas and threatened with a criminal indictment over his testimony surrounding the Fed’s building renovation project. Calling it an “unprecedented action,” Powell contended that the federal inquiry was “a consequence” of the Federal Reserve not lowering interest rates.

Many Democrats –– as well as some Republicans –– criticized the investigation as assault on the independence of the Fed. For his part, Trump said that he did not know about the probe into Powell.

Talley and Braun pointed to historical examples of other countries where politicians have steered central banks’ decisions, leading to high inflation.

“The Federal Reserve needs to be independent for the very reason why Trump wants them to be dependent,” Braun said, “They need to be independent because we need interest rates set according to what’s best for the long-term path of the economy.”

In his remarks last year, Powell has repeatedly emphasized the Fed’s dual mandate: to foster maximum employment and price stability. However, economic indicators have seemed to point toward opposite courses of action, he noted.

Consumer prices rose 0.3% last month from November, according to the most recent report released by the Labor Department. The figures showed a modest increase in the Federal Reserve’s preferred gauge –– with inflation remaining above the Fed’s 2% target.

Meanwhile, the most recent monthly jobs report released by the Commerce Department showed sluggish hiring in December even as unemployment remained low.

Last year, the Federal Open Market Committee voted to lower interest rates three times, each by a quarter of a percentage point. The group is next slated to meet at the end of January, and it’s unclear how it will vote.

Kedia suggested that markets may be left wondering –– should there be another cut –– if the decision was solely based on economic data. He also noted that some data was not collected and reports delayed during last fall’s government shutdown, adding another layer of uncertainty.

And Monarch suggested that the pressure applied by the White House could also create speculation in the other direction –– should the Fed keep the rate unchanged –– that the central bank may be seeking to assert its independence in contrast with the president’s wishes.

“There might be some pressure to show that you want to be doing something different than what the administration wants you to do,” he said, noting that Powell’s term is up in May, and after which, “It’s hard to imagine politics sort of being completely escapable from the Feds’ decisions.”

Separately, Trump also attempted to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook in August over allegations of mortgage fraud, which Cook denies –– a move never undertaken by a president in the agency’s 112-year history. The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments about Trump’s ability to fire Cook Wednesday.

“President Trump seems to have a very, very strong incentive to bring the Federal Reserve under his direct control,” Talley said. “So this is a showdown that has certainly begun in earnest, but my guess is it’s going to be playing out over the next few months, and that does increase the amount of uncertainty that we face as well.”

President Donald Trump signs his signature bill of tax breaks and spending cuts at the White House, July 4, 2025, in Washington, surrounded by members of Congress. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

The tax cuts and spending bill

On July Fourth, Trump signed into law his One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The legislation extended trillions of dollars of 2017 tax cuts that had been scheduled to expire, removed taxes on tips and reduced federal spending by an estimated $1.4 trillion, mostly from programs such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and federal student loans. The law also upped other spending –– largely on the military and immigration enforcement -– by $325 billion.

The legislation, along with the tariffs and actions such as seeking to cap credit card interest rates, reflected what Monarch described as a “mixed bag” of priorities — combining traditional Republican initiatives like tax cuts with ones that have been historically policies of the other side of the aisle.

“If you were to substitute President Trump with a different member of the Republican Party as president, you would probably see a lot of the same policies on the tax cutting and regulation cutting that we see,” he said. ”And you wouldn’t see some of these other policies that President Trump is also doing.”

The Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that Trump’s signature tax cuts and spending bill would increase the federal deficit by $3.4 trillion over the next 10 years.

Trump has said tariff money will be used to pay down that shortfall –– while also floating a proposal to use tariff revenue to send checks directly to Americans.

“Trying to use those (tariffs), trying to drive a wedge into our trade market, and then using that to pay for our original sin, which is government spending, seems to be a foolish idea to me,” Kedia said. “In that respect, it makes much more sense to be much more fiscally responsible, spend less.”

Talley said that the legislation will end up “placing some significant strain on U.S. federal budgets” and noted that Republicans traditionally have been “pretty hawkish on deficits.”

“President Trump’s a very unconventional approach from the standpoint of traditional Republican economic policies,” Talley said. “The shifting sands of what does the Republican Party stand for now, in a year, in two years is also kind of adding to the mix of unpredictability that we’re now …. intertwined with.”

Credit: Source link